After a routine kernel update and reboot, my Ubuntu system came back without any network connectivity. No Ethernet. No fallback. No warning. Just silence. What followed was not a quick fix, but deep troubleshooting. And the conclusion was uncomfortable.

This was not a misconfiguration.

This was not systemd.

This was not netplan.

This was not even really Ubuntu.

This was a design boundary in Linux that is rarely explained clearly.

The setup that looked perfectly reasonable

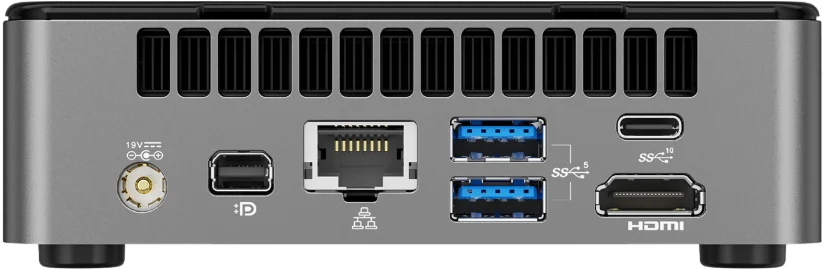

The system used an onboard Motorcomm Ethernet controller. On Linux, this NIC requires an out of tree driver installed via DKMS. Everything worked. The driver was installed. Networking was stable. The system rebooted fine. Until it did not. Then a kernel update happened. After reboot, the network interface was simply gone.

No errors on screen.

No warning during upgrade.

No rollback.

Just no NIC.

The real culprit was not the kernel update

At first glance it feels logical to blame the kernel update. But that is not the real problem.

The real problem was this combination:

An out of tree DKMS network driver

Secure Boot enabled

Only one critical network interface

Automatic kernel updates

No rollback or fallback path

That combination is fragile by design.

Linux allows you to build such a system, but it does not protect you from the consequences.

Secure Boot is not a stability feature

Secure Boot protects against boot chain tampering and physical attacks. It does not protect availability. It does not protect remote access. It does not protect you from broken drivers. In fact, when combined with DKMS drivers, Secure Boot can silently block essential hardware without clearly telling you why. From a security perspective that behavior is consistent. From an operational perspective it is brutal. Security and availability are different goals. Secure Boot prioritizes security every time.

In tree drivers versus out of tree drivers

This incident finally forced me to deeply understand a concept that is often mentioned but rarely emphasized enough. In tree drivers are part of the Linux kernel itself. They are built together with the kernel, tested together, and updated together. They survive kernel upgrades because they are the kernel. Out of tree drivers live outside the kernel. They depend on matching headers, toolchains, signing, and rebuilds. When something changes, they can break. Sometimes silently. My network depended on an out of tree driver. That was the real mistake.

The professional lesson

There is an old rule in professional Linux operations: Never rely on DKMS for your only network interface on a system that must remain reachable. I had violated that rule without realizing it. Ubuntu did not fail me. The kernel did not betray me. I stepped outside the safe support envelope and assumed the system would still protect me. It did not.

The practical fix

The solution was not more debugging. The solution was architectural. I added a USB to Ethernet adapter using a Realtek chipset with an in tree driver. No DKMS. No signing. No surprises. mmediately the system became boring again. Reboots worked. Kernel updates worked. Secure Boot no longer mattered. That USB NIC is now my lifeline. And I trust it far more than the onboard controller.

What I changed permanently

I made several decisions after this experience. I no longer rely on out of tree drivers for critical access paths. I keep at least one previous kernel installed at all times. I question Secure Boot in contexts where availability matters more than physical tamper resistance. I treat kernel updates as controlled events on systems that can lock me out. Most importantly, I no longer assume that stability means fail safe behavior.

Why I am writing this

Because this kind of failure is not obvious until it happens. Because many users will hit this once.

Because Linux documentation rarely connects these dots clearly. And because frustration is wasted if it does not become knowledge. Linux is powerful. But power comes with responsibility. And sometimes, with sharp edges.